The Gruaro massacre

This article also contains the Podcast version of the interview with Angelina, a lady born in 1925, who survived the Gruaro massacre. We advise you to listen to her interview after reading the editorial.

Do you want to listen to this article in podcast version? (click to open)

Interview with Angelina, survivor of the Gruaro massacre

If you want to listen to all our podcasts, follow us on spreaker.com

Download the editorial in PDF

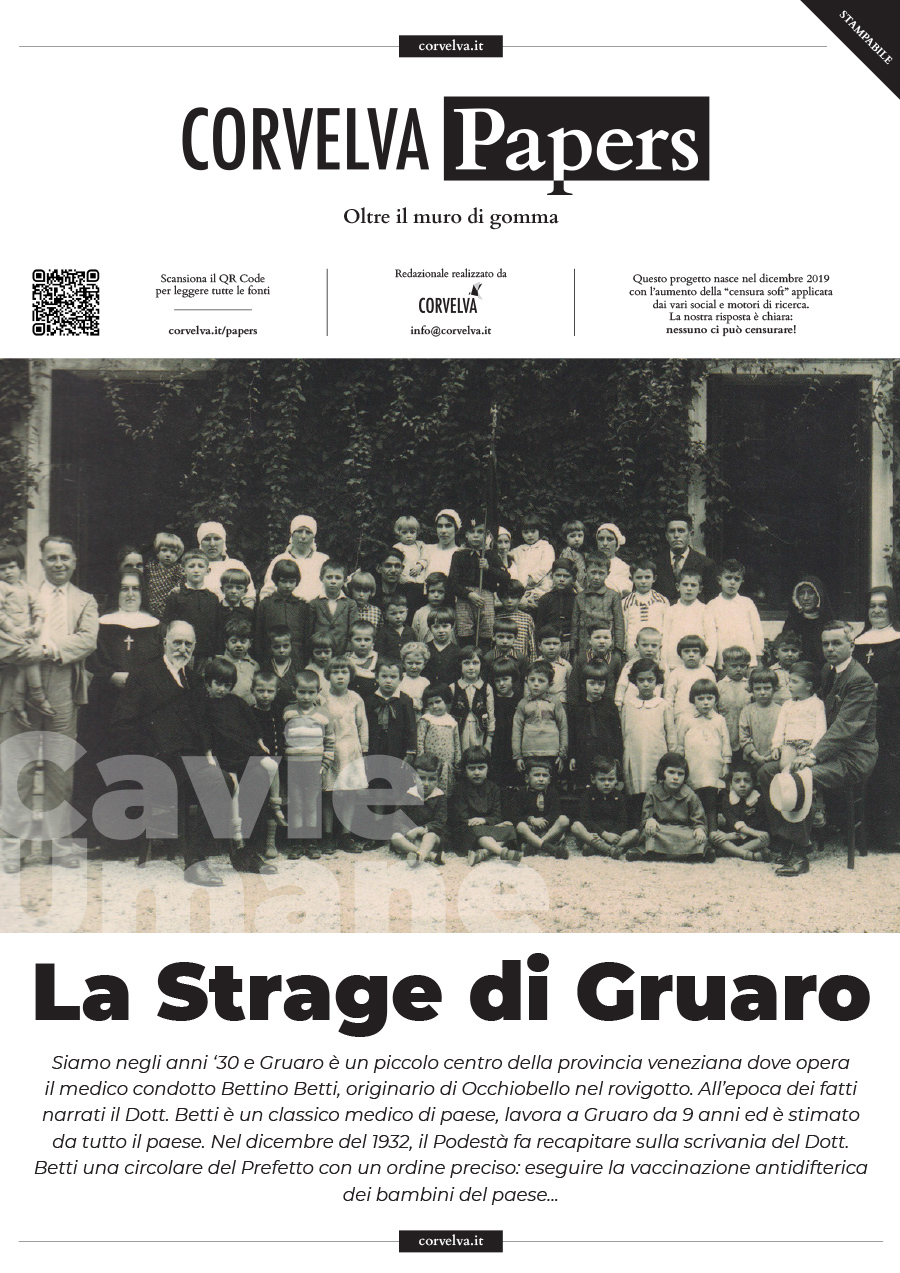

The tragic story we are telling was exhumed from the oblivion of history thanks to Adamo Gasparotto, born in Pradipozzo di Portogruaro in 1928 and raised in Gruaro. Gasparotto is a survivor of the “Gruaro children's massacre” and managed to stir consciences through newspaper articles and ultimately also the municipal administration of the town to remember the victims of an anti-diphtheria vaccination campaign carried out in 1933. A book commissioned by the Municipality of Gruaro on the affair, as well as the two commemorative plaques on cemetery chapels where "i fioi de la pontura" rest, are thanks to his determination and desire for truth. Our editorial is dedicated to him, as to all the children victims of that madness.

The tragic story we are telling was exhumed from the oblivion of history thanks to Adamo Gasparotto, born in Pradipozzo di Portogruaro in 1928 and raised in Gruaro. Gasparotto is a survivor of the “Gruaro children's massacre” and managed to stir consciences through newspaper articles and ultimately also the municipal administration of the town to remember the victims of an anti-diphtheria vaccination campaign carried out in 1933. A book commissioned by the Municipality of Gruaro on the affair, as well as the two commemorative plaques on cemetery chapels where "i fioi de la pontura" rest, are thanks to his determination and desire for truth. Our editorial is dedicated to him, as to all the children victims of that madness.

Adamo Gasparotto, 1928-2021

Adamo Gasparotto, 1928-2021

We are in the 30s and Gruaro is a small town in the Venetian province where the medical doctor Bettino Betti, originally from Occhiobello in Rovigotto, works. At the time of the events narrated, Dr. Betti is a classic village doctor, he has been working in Gruaro for 9 years and is respected by the whole country. In December 1932, the Podestà had a circular from the Prefect delivered to Dr. Betti's desk with a precise order: carry out the anti-diphtheria vaccination of the children of the town. At the beginning the doctor, perhaps feeling deprived of his role, also opposed it quite decisively and responded to the Podestà's order with a letter to justify his opposition to subjecting the children, his clients, to vaccination: “I have the honor to inform you that I did not believe it appropriate in the past, nor would I consider, if nothing else happens, it appropriate even today to practice diphtheria vaccination on children, due to the fact that in the last three years only two have been reported to the Royal Prefecture of Venice cases of croup (barking cough, a symptom of diphtheria, ed.) and that even currently the general conditions of the population with regard to this disease are more than satisfactory" (Gruaro 24-12-1932).

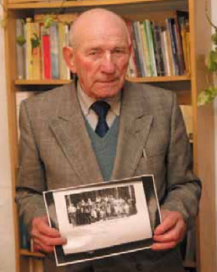

The last mass vaccination carried out in the country dates back to 1918 and was smallpox, made compulsory in 1888. For diphtheria the vaccination practice was still relatively recent and for some years the vaccine of the French biologist Leon Gaston Ramon, dating back to 1923/1925, which included a cycle of 3 inoculations.

Gaston Leon Ramon, biologist and veterinarian of the Pasteur Institute,

Gaston Leon Ramon, biologist and veterinarian of the Pasteur Institute,

father of diphtheria anatoxin

Let us remember that diphtheria is a contagious disease caused by the bacterium Cornybacterium diphteriae, which mainly affected the throat and upper respiratory tract and was linked to various complications, even very serious ones, especially in a rural society with truly basic health services. Although aware of the dangers of the disease, Dr. Betti nevertheless remains pragmatic: there are practically no cases of diphtheria in the Venetian area and the specialists of the time were quite divided on whether or not to extend these vaccinations outside of epidemic outbreaks.

The doctor who will inject the deadly poison of the Gruaro massacre is not among the ranks of the first fanatical followers of the incipient standardization of vaccination practice. He is a country doctor, pragmatic, and at first he even shows a certain determination against the higher orders that he considers not sensible. A determination that, as we will soon see, will not last long. The village rumors about Doctor Betti's opposition to vaccination probably date back to this interlude, between the doctor's response and the subsequent vaccination. Annoyance vanished as if by magic in the space of a few weeks.

Prefect Bianchetti (the true director of these events) at the beginning of January 1933, regardless of Betti's complaints, gave instructions to the Podestà to comply with the Ordinance and, furthermore, imposed that the vaccination be carried out with the vaccine supplied by the National Institute Serotherapy of Naples, directed by Prof. Terni.

This aspect of the prefectural provisions is of no secondary importance for the interpretation of the events that will take place shortly thereafter. The “Terni” vaccine was obtained with a culture method different from the “Ramon” for the production of toxins with a high antigen value and involved a single injection instead of the 3 canonical ones associated with 2 rather painful Schick controls. The dose that the Terni Institute generally proposed in those years was triple compared to the single injections of Ramon; in some experiments, however, it provided tenfold doses.

The Prefect indicates Prof.'s "experimental" vaccine for Gruaro. Terni produced in Naples, while the other nearby municipalities, such as Cordovado or Portogruaro itself, continued to obtain supplies from the Milan Institute or the Tuscan Vaccination Institute, which used the Ramon vaccine.

The day established by the Prefect for the start of the vaccination campaign was 20 March 1933. From that moment on, all children aged 13 months to 8 years in the municipality of Gruaro will have to be inoculated with anti-diphtheria.

At this point the doctor of command Betti must choose: clash with the mayor and the prefect for a vaccination which is not required by law, or comply with orders from above. She chooses to comply. The Doctor, against the "usual" vaccination, must now become the standard bearer of this "new" one, about which he has no reliable information from the scientific literature on the subject, as he will explain to the Provincial Doctor. Furthermore, he must above all convince his clients to take their children to the injection.

It must not be easy in the village to publicly be Terni's standard bearer, when in private even Ramon is doubted. And so ours goes quickly, as those former children who survived his inoculations remember.

“Dr. Betti put very strong pressure on families to convince them to have the shot, sometimes using the weapon of blackmail: those who do not take their children for vaccination could be excluded from medical assistance” (Testimony by Maria Danielon in Modenese, born in 1926 ). As you can see, vaccination and blackmail have a long history in the "medical" field.

Five days before the start of the operations, on 15 March 1933, Dr. Betti wrote a letter to the Provincial Doctor of Venice in which the awareness of actively participating in an experiment shines through, almost in filigree: "I have the honor to inform you that under the date on March 20th the vaccination with the prof's diphtheria anatoxin will begin. Terni single dose for hypodermic use. Once the operation is completed, the undersigned will take care to provide this Superior Office with all the information relating to it. Fascist regards Dr. Betty."

Even the parish priest, Don Cuminotto, seals the alliance between throne and altar by inviting families from the pulpit of the mass to be vaccinated against diphtheria. The priest diligently travels around the country going to the most recalcitrant families to convince them of the absolute necessity of the injection. This act of collaboration will cost him the resentment of many fellow citizens (as well as not-so-veiled threats once the tragedy is over). Who knows if he too described the Terni vaccine as an "act of love", before it caused impairment and death of the souls of which he was the guardian.

Dr. Betti had his clinic in Gruaro inside a large building which also housed the Town Hall in one wing and the school classrooms in the other. For the children of Gruaro and Bagnara (a hamlet of the town) the vaccination takes place from the clinic to the classroom without even having to leave the building. The vaccination program is very dense: On Monday 20 March 47 children were vaccinated, Tuesday 92, Wednesday 48, Thursday none, break, Friday 10, Saturday 33, Sunday all at mass and another break, the following Monday 28 and Tuesday 28 March the last 3. 254 children vaccinated in 9 days (the three daughters of the municipal secretary who did not show up at school were missing).

From the first days, however, something didn't go right. Returning home after the injection, or the day after, some children can no longer stand upright and suffocate while eating as emerges from the testimonies of Vittorina Colautti, born in 1928, and Adamo Gasparotto: "The parents begin to ask the doctor for explanations who, however, supports that what is happening to us is not caused by the vaccine and indeed continues to do so to all scheduled children."

Giuseppe Colautti (Beppino) is among the 47 children vaccinated on the first day, he begins to feel ill immediately, he no longer walks well (he will end up dying on April 28th). Dr. Bettino Betti, however, continues to silence all those parents who came to ask for explanations: "no correlation", was the answer to everyone.

As the vaccination program progresses, some of the older children escape out the window when doctor Betti arrives in class, while others don't show up at all. More and more voices tell of families whose children were ill after the shot. Betti's counter-move consists of locking the doors and windows of the classrooms as soon as he enters to vaccinate.

Faced with these facts, something begins to change in the doctor's attitude. There are no longer only doubts about the usefulness of vaccination, he has before his eyes the first evidence on the absolute lack of safety of the injected doses, but he proceeds anyway and his adherence to the wishes of the Prefect of the Regime is now total.

On the same evening of March 28, having finished with the children of Gruaro and Bagnara, he sent his report to the provincial doctor as promised and did so even before proceeding with the hamlet of Giai, a hamlet further away than Bagnara and for which it was necessary to organize moving the clinic to the site. While in front of patients he shows absolute determination, denying the correlations with the numerous illnesses in children, with his superiors he becomes more doubtful, worried and uncertain. In the doctor's report Betti, in addition to congratulating the success of the operation because "The Provision, first illustrated in the church by the individual parish priests of the Municipality, met with great public approval", reports having found vaccine damage such as: “erythema, rashes, urticaria, edema, fever, very annoying and sometimes frankly worrying, persistent digestive disorders”. The doctor was worried but not enough to clearly explain all the problems found. The “very tenacious digestive disorders” were actually the difficulties in swallowing described in almost all the survivors' testimonies and the vomiting from the nose. Furthermore, he makes no mention of the most worrying symptom of which he was immediately made aware: difficulty walking or the inability to stand. In short, it removes from the report all adverse neurological events.

He prescribes calcium chloride, considered the antianaphylactic par excellence, and ichthyol compresses to all those affected, but makes no mention of the fact that towards the end he begins to inject half a dose. In fact, Pietro Bigattin, born in 1930, says that on Friday the 25th “Since previously vaccinated children are ill, when it is my turn, Doctor Betti only injects me with half a dose of the vaccine. The consequence, however, is a very high fever, which makes me jump on the bed like a spring".

A couple of weeks later the Prefect suspended the vaccination and on April 9th there was even an inspection by the provincial doctor aimed at personally ascertaining the conditions of the sick children after the injection. We do not know what he found in this visit since the Regime made a large part of the documentation on this episode disappear from both the municipal and ministerial archives, except for two telegrams from Betti sent to the Provincial Doctor which tended to reassure, again, about the "good health” of the 253 vaccinated children and that “the reactive phenomena, although sometimes impressive, resolved happily”.

From here on out it is a war bulletin: the children begin to get worse at the same time, revealing the rainbow of discomfort in all the most serious forms: blindness, high fever, inability to swallow, pain in the legs, paralysis at various levels, boils on the whole body. Only at this point does Dr. Betti start sending telegrams in rapid fire asking for "counterpunctures" (antibodies capable of blocking the live vaccination virus), which do not arrive in sufficient quantities and in any case are unable to stop the degenerative processes in progress . All 254 vaccinated children are hospitalized: the most seriously ill in the hospital in Padua and in Portogruaro and the others in the municipal dispensary. From April 24th to May 16th there were 28 deaths, 13 males and 15 females. It seems that in many cases the youngest ones died. Three families who will unfortunately lose both children. Some will be scarred for life, other survivors remember the recurrence of problems even many years later.

Another emergency department is set up in front of the Difesatto hotel in Portogruaro (former headquarters of Credito Veneto)

Another emergency department is set up in front of the Difesatto hotel in Portogruaro (former headquarters of Credito Veneto)

A good part of the witnesses agreed in recalling the hatred in the town towards the doctor Bettino Betti. Some families threatened him with death and we remember a procession of women towards the municipality/school/clinic with sticks in their bags. The Prefect even entrusted him with a Carabinieri escort to save him from his fellow villagers.

Doctor Betti will be forced to move house, move to Portogruaro and leave the Gruaro conduct permanently in 1937. His initial opposition to vaccination - which he will always invoke as an excuse for his "good faith" - will not save him from the eternal blame of his fellow villagers. One of these will summarize this figure like this: “Many people say about the doctor Betti that he is a lazy boy, but he defends himself by stating that he was forced and continually repeats I didn't want to do it... I didn't want to do it! The prevailing popular voice claims that the authorities wanted to carry out an experiment and he was not determined enough to resist” (Gina Zanon, born in 1919).

The true director of this massacre and political responsible for the tragedy, the prefect Giovan Battista Bianchetti, left the lagoon in September 1933 having been promoted as head of cabinet of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers. The Regime blames the incident on a poorly prepared batch of vaccine, closes the Serological Institute of Naples, arrests the professor. Terni and his assistant Testa. The professor will not undergo any trial and will die from a simple fall down the stairs within a few months, presumably free.

The Stefani Agency, the regime's press agency, spoke of only 10 deaths and then silenced all the newspapers that tried to report on the Gruaro episode, followed and surpassed in this cover-up by the Catholic press, which allows only a few lines to filter through without ever mentioning any dead person.

The memorial to the children victims of the experimental vaccination of 1933, Bagnara cemetery.

The memorial to the children victims of the experimental vaccination of 1933, Bagnara cemetery.

Plaque in memory of the children of Bragnara, at the municipal cemetery.

Plaque in memory of the children of Bragnara, at the municipal cemetery.

Don Cuminotto and Doctor Betti were even awarded the title of Knight of the Order of the Crown by Vittorio Emanuele III.

The historiographical debate on the Gruaro massacre was mainly focused on the question whether Prof. Terni's vaccine, sent by the National Serotherapy Institute of Naples, had been poorly prepared due to a tragic error (version accredited by the Fascist Regime at the time) or the result of conscious experimentation by the authorities. It was later noted from Doctor Betti's records that Gruaro's vaccines were lethal with a percentage that fluctuated between 12,7 and 20% (depending on the day).

Avoiding the hypotheses of different batches arriving in Gruaro, the hypothesis we can make is that the mortality depended on the quantity of dose injected by the doctor. Having reached the fifth day of vaccination, faced with the myriad of reports received by the doctor of adverse events in the days before, one child received only half a dose of vaccine which in any case led him to feel ill, but not to the point of dying. It is quite probable that the awareness of the amount of damage he was causing to the children led Doctor Betti to reduce the dose not only to Pietro, that child who retained his memory and told the story of what had happened, but also to all the others. This would explain the zero mortality following Friday the 24th.

The Regime wanted a single-injection "Italian" vaccine and tested it on unsuspecting children from the Veneto province like Gruaro, but probably also from other places: children from Cavarzere also ended up in hospital in Padua due to the effects of anti-diphtheria. In the edition of 3 May 1933, the newspaper "Roma", which is printed in Naples, gives the news of the closure of the National Sierotherapy Institute of Terni and the tragedy of Gruaro, together with other "disturbances" of the same kind but more minor which have occurred in vaccinated children in some municipalities in the Milanese, Varese, Genoese and Treviso areas.

Bowing to the atrocities of power is generally comfortable. Sometimes it leads to massacres. Resisting is complicated and always involves a price to pay as the case of Doctor Sergio Borellini teaches us who in 1933, as a general doctor of Portogruaro, rushed to help his colleagues from Gruaro and then to the hospital to treat the affected children.

He will be a dissonant voice in that massacre, which cost him a lot since he was accused of having expressed his opposition to vaccination in public, thus bringing discredit to the doctor Betti and the authorities. A few months after these events he underwent disciplinary proceedings at the instigation of the Podestà and the Prefect, the so-called Censura.

Many remember that Dr. Borellini motivated his opposition to this vaccination by testing the serum on a rabbit, which died immediately after the shot. His opposition to this and other vaccinations guaranteed him the gratitude of his fellow citizens, he was an example of love for his profession. The contrast, in the memory of the country, between the two doctors, was still very vivid after many years. Borellini will conclude his professional life with the gold medal for honorable service awarded by the Municipality in 1975 in his conduct of Portogruaro. His daughter Mirella remembers that his father often spoke of his critical attitude towards the vaccinations imposed by the authorities: "When he wasn't convinced he pretended to inoculate the vaccine because he only put water in the syringe".

In Gruaro the population will no longer undergo any vaccination for a very long time, not even after 1939, when anti-diphtheria became mandatory by law, but the events that occurred in that year, as some survivors told us, were a sort of damnatio memoriae. It wasn't supposed to be talked about in the family, in the countries it was taboo to remember and in a short time the true and only holders of that memory, the children, buried that tragedy in their memories, making it re-emerge like a thunderclap 70 years later.

This attitude, also told by Angelina, a lady born in 1925 whose interview you will find on our website, brings us back to today and to what parents of vaccine-damaged children experience: facing and living with a sort of sense of guilt . It is something known in psychology, the sense of guilt of victims of injustices or atrocities of various types. Let's be clear to everyone, it's not the parents' fault, but saying it isn't enough. This mechanism is a major obstacle that acts as a deterrent even today in dealing with vaccine damage or investigating it as a possible cause of various kinds of disabilities or health problems for one's child. Now, to return to 1933, you have to imagine the rural society of the time, made up of that peasant simplicity that characterized the Venetian province. Many children began to hear those terrible stories and began to run away from school. Children aged 6-8 years, who ran away together in the fields, hiding in the pigsties to avoid being bitten. All promptly recovered by the parents who had not yet fully understood the extent of the problem. This could be the real reason why, in addition to regime censorship, the Gruaro massacre remained buried for decades. The terrible truth is that many of the dead children had been "fished out" from the camps by their parents and brought to Dr. Betti. This inconvenient truth should be taken as an element to explain the long silence on this event and certainly not to place blame on the poor parents. It is obvious that the families of the victims had no guilt nor, obviously, adequate information: they were tricked and deceived, used for an experiment, forgotten and abandoned by the same institutions that claimed their trust.

Unfortunately, history repeats itself and the importance of remembering and bearing witness to these facts also and above all lies in not allowing them to fall into oblivion: therefore the experiment carried out on the skin of innocent victims is nothing new, the sales pitch with lies of the popular masses, nor the indifference of local and state institutions to the consequences of such misdeeds. Unfortunately, it is nothing new, not even the pain caused with superficiality and indifference by the arrogant Power that treats the population as a flock to be managed as it pleases, using conviction as much as arrogance, blackmail, obligation, coercion.

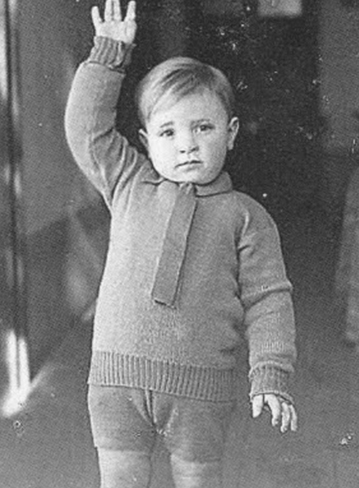

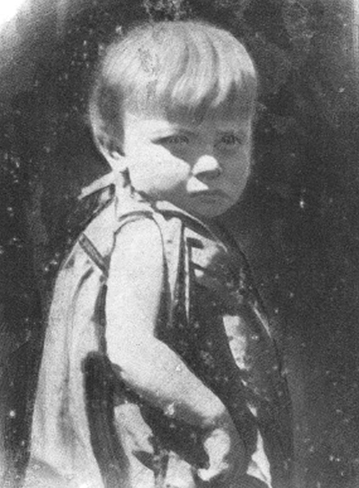

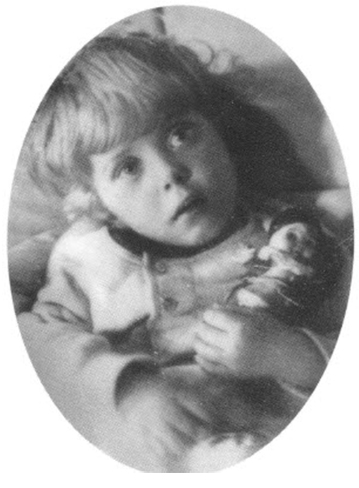

Some of the young victims

Mario Zanin, born on 24/5/1931, died on 30/4/1933

Mario Zanin, born on 24/5/1931, died on 30/4/1933

Plinio Paschetto, born on 11/8/1931, died on 26/4/1933

Plinio Paschetto, born on 11/8/1931, died on 26/4/1933

Plinio Peresson, born on 12/05/1931, died on 24/4/1933

Plinio Peresson, born on 12/05/1931, died on 24/4/1933

Bruno Paschetto, born on 20/2/1928, died on 6/5/1933

Bruno Paschetto, born on 20/2/1928, died on 6/5/1933

Battista Dreon, born 25/06/1930, died 8/5/1933

Battista Dreon, born 25/06/1930, died 8/5/1933

Sira Toneatti, born on 14/2/1931, died on 1/5/1933

Sira Toneatti, born on 14/2/1931, died on 1/5/1933

Maria Orlando, born on 10/5/1930, died on 9/5/1933

Maria Orlando, born on 10/5/1930, died on 9/5/1933

Caterina Zambon, born on 12/11/1930, died on 15/5/1933

Caterina Zambon, born on 12/11/1930, died on 15/5/1933

Florida Toneatti, born 11/7/1927, died 8/5/1933

Florida Toneatti, born 11/7/1927, died 8/5/1933

Maria Marson, born 19/4/1931, died 1/5/1933

Maria Marson, born 19/4/1931, died 1/5/1933

Luigi Bonan, born on 26/6/1927, died on 3/5/1933

Luigi Bonan, born on 26/6/1927, died on 3/5/1933

Iole Toffoli, born on 4/12/1930, died on 09/5/1933

Iole Toffoli, born on 4/12/1930, died on 09/5/1933

Giovanni Bovo, born on 12/1/1932, died on 28/4/1933

Giovanni Bovo, born on 12/1/1932, died on 28/4/1933

Luciano Stefanuto, born on 8/1/1932, died on 28/4/1933

Luciano Stefanuto, born on 8/1/1932, died on 28/4/1933

Complete list of dead children

| Surname and name | Date of birth | Death date | |

| 1 | Barbui Erminio | 23/12/1929 | 13/05/1933 |

| 2 | Bass Maria | 22/02/1932 | 28/04/1933 |

| 3 | Biason Placida | 19/03/1931 | 04/05/1933 |

| 4 | Bonan Luigi | 26/06/1927 | 03/05/1933 |

| 5 | Bortolussi Mirella | 13/06/1926 | 16/05/1933 |

| 6 | Well done John | 12/01/1932 | 28/04/1933 |

| 7 | Colautti Giuseppe | 28/12/1929 | 28/04/1933 |

| 8 | Falcomer Evelina | 23/08/1931 | 25/04/1933 |

| 9 | Innocent Celsus | 21/10/1931 | 02/05/1933 |

| 10 | Moro Antonietta | 17/01/1929 | 06/05/1933 |

| 11 | Nosella Iole | 17/09/1931 | 04/05/1933 |

| 12 | Peresson Pliny | 12/05/1931 | 24/04/1933 |

| 13 | Stefanuto Luciano | 08/01/1932 | 28/04/1933 |

| 14 | Stefanuto Imelde | 19/05/1929 | 11/05/1933 |

| 15 | Toffoli Iole | 04/12/1930 | 09/05/1933 |

| 16 | Toneatti Florida | 11/07/1927 | 08/05/1933 |

| 17 | Toneatti Sira | 14/02/1931 | 01/05/1933 |

| 18 | Zambon Caterina Anna | 12/11/1930 | 15/05/1933 |

| 19 | Zanon Celia | 23/03/1927 | 16/05/1933 |

| 20 | Biasio Renato | 30/04/1931 | 26/04/1933 |

| 21 | Dreon G. Battista | 25/06/1930 | 08/05/1933 |

| 22 | Marson Mary | 19/04/1931 | 01/05/1933 |

| 23 | Orlando Maria | 10/03/1930 | 09/05/1933 |

| 24 | Paschetto Bruno | 20/02/1928 | 06/05/1933 |

| 25 | Paschetto Plinio | 11/08/1931 | 26/04/1933 |

| 26 | Romanin Edda | 27/06/1931 | 27/04/1933 |

| 27 | Romanin Sante | 31/05/1930 | 08/05/1933 |

| 28 | Zanin Mario (Second) | 24/03/1931 | 30/04/1933 |

Sources (click to open)

- Dario Bigattin, The cursed Sting of 1933, Municipality of Portogruaro, Portogruaro (VE) 2014.

- Paolo Riccardo Oliva, Gruaro's children were an experiment. History and memory of a massacre (1933-2015), Venetica 2018 – 54, page. 89-122.

- Ariego Rizzetto, Gruaro, twenty centuries of history, Municipality of Gruaro, Gruaro 2004, p. 234-236.

- Adamo Gasparotto, Open Letter, Spinea 1 September 2013.

- Gian Piero del Gallo, FThere was a photo for the tombstone but I survived, La Nuova Venezia, 5 December 2013.

- Adamo Gasparotto, The vaccine for meningitis and the Gruaro massacre of 1933, Il Gazzettino, 7 January 2008.

- Gabriele Pipia, Gruaro massacre, the deadly vaccine also hit Venice, Il Gazzettino, 8 December 2013.

- Venezia Today, 02 December 2013, «We, children chosen as guinea pigs». The truth about the Gruaro massacre of '33, https://www.veneziatoday.it/cronaca/strage-gruaro-2933-bambini-morti-vaccino.html

- https://www.ogginotizie.eu/attualita/quel-dottore-che-salvo-migliaia-di-bimbi-rifiutandosi-di-vaccinarli/

- http://www.laruotagruaro.it/edit/per-amore-di-verita

- Direct interviews with Gruaro survivors

- https://www.veneziatoday.it/persone/adamo-gasparotto/

- http://www.laruotagruaro.it/edit/per-amore-di-verita